OKLAHOMA CITY (BP) — At 9:02 a.m. Wednesday, April 19, 1995, a huge explosion rocked downtown Oklahoma City, and a pillar of black smoke soared into the bright azure sky above the center of the state’s capital. Shocked and stunned residents watched in disbelief, wondering what had happened.

Thanks to almost immediate television coverage, it took only a few minutes for most residents to learn that the explosion was the result of a bomb placed in a 24-foot Ryder rental truck parked in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.

It was determined later that Timothy McVeigh, a disgruntled former U.S. serviceman, carried out the bombing that killed 168 people, as well as three unborn babies, and injured more than 680 others. The bombing was the deadliest act of terrorism in the United States prior to the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

McVeigh was arrested shortly after the bombing and indicted on 160 state offenses and 11 federal offenses, including the use of a weapon of mass destruction. He was found guilty on all counts in 1997 and sentenced to death. He was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001. Co-conspirators Terry Nichols and Michael Fortier were also convicted. Nichols was sentenced to eight life terms for the deaths of eight federal agents, and to 161 life terms without parole by the state of Oklahoma for the deaths of the others. Fortier was sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment and was later released.

At the time of the blast, the Murrah Building housed some 600 federal and contract workers, as well as an estimated 250 visitors. The explosion was the most destructive — and costly in the terms of lives taken — act of domestic terrorism carried out in U.S. history. The blast was felt as far as 30 miles away and damaged 347 buildings in the immediate area. Thirty buildings were heavily damaged. In the aftermath, almost 20 buildings were torn down. Twenty blocks of downtown Oklahoma City were cordoned off due to the extent of the bomb damage.

Tragically, among the lives lost that spring morning were 19 children under the age of 6 being cared for in the America’s Kids Day Care Center on the second floor. The total number of lives lost would increase by one with the ensuing death of a first responder — nurse Rebecca Anderson — who died as the result of a piece of concrete striking her in the back of the head while she was helping rescue survivors.

Two decades earlier, Oklahoma Baptists had made preparations to respond to disasters. The state had been divided into four areas, each with a team of volunteers under the supervision of an area leader. This enabled more volunteers to become involved in ministry without calling the same team to respond time after time. All volunteers and leaders of the four areas were called upon to help in the Oklahoma City bombing.

According to the 1995 Oklahoma Baptists Annual Report, 55 disaster relief volunteers prepared approximately 6,000 meals for rescue workers, and 21 volunteers provided emergency daycare at a nearby shopping center for 11 days. A total of 93 children were given supervised care at the request of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

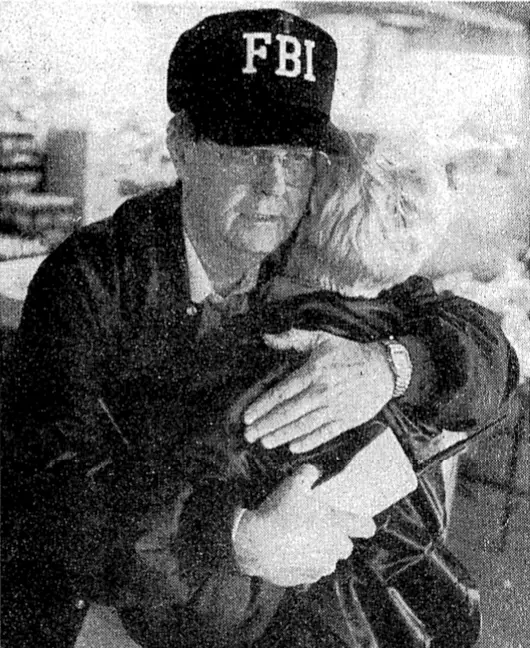

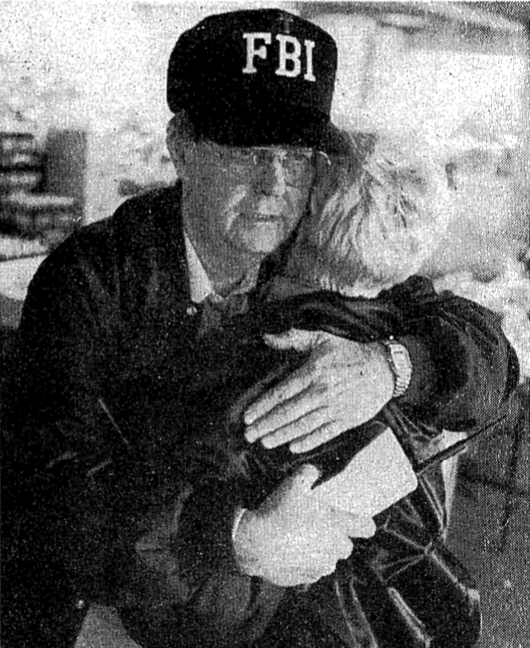

Oklahoma Baptists’ chaplaincy program officially was organized in 1984 by Bob Haskins, and in 1986, Joe Williams, pastor of First Baptist Church of Nicoma Park, was brought on board as chaplaincy and community services specialist. Under Williams’ direction, chaplaincy grew in many areas. As the dust and smoke from the destroyed Murrah building was settling, Southern Baptist chaplains — including Williams, Oklahoma City Police Department chaplain Jack Poe, Oklahoma City Fire Department chaplain Ted Wilson and Cleveland County Sheriff’s Office chaplain Paul Bettis — ministered to teams searching the Murrah Building for survivors.

Bettis, who also was working in prison chaplaincy at the time, later served as Oklahoma Baptists’ chaplaincy specialist from 2002-2013. As the bombing response continued, he was involved, along with officers with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, in serving death notifications to family members.

Wilson, the fire department chaplain, was kept busy 16-18 hours a day, leading continuous critical incident stress management sessions. He said 985 firefighters participated in the rescue and recovery effort after the bombing. In addition, there were about 250 police officers. All told, more than 25,000 people worked the site, he said.

Williams, who died in 2016 from bladder cancer, later represented Oklahoma Baptists as a member of the committee that distributed donated funds to survivors and victims’ families. Also serving on that distribution committee was Wilson, who recently retired as the city’s fire department chaplain after serving in that capacity for 30 years.

Anthony L. Jordan, now retired executive director-treasurer of Oklahoma Baptists, and pastor of Oklahoma City, Northwest at the time of the bombing, wrote 20 years after the tragedy in his Perspective column in the Baptist Messenger that, “In the hours and days that followed the bombing, one thing became clear. Oklahoma faced tragedy in a different way than had been evidenced in other parts of the country and world. Volunteers, companies and first responders rushed to the site, offering themselves, equipment, food and anything needed to help with the search and rescue effort…. No need went unmet.”

Bob Nigh is Historical Secretary of the Oklahoma Baptist Historical Commission.

This article was originally published by Baptist Press at bpnews.net